Satellites

galaxy evolution of satellites in groups and clusters

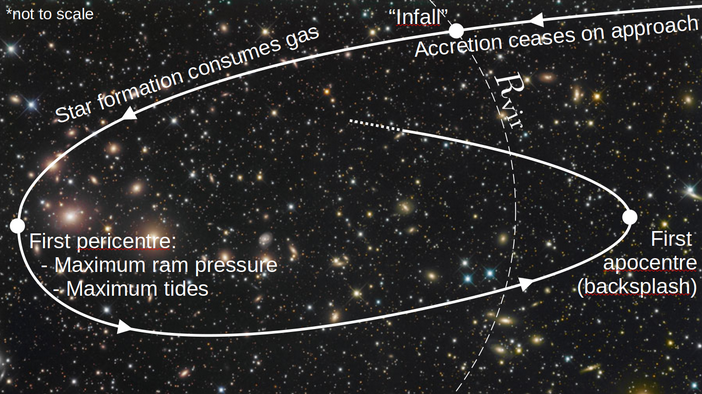

I started my journey in astrophysics research with my MSc project. Well, technically I wrote a halo finder for my BSc Honours project - it wasn’t very good. The goal was to connect the orbital histories of satellite galaxies within galaxy groups and clusters with their star formation histories. There are a host of physical processes that affect satellites - the idea is that by connecting the star formation history to the orbit, we should get hints as to which processes are dominant in regulating the star formation cycle. Schematically some of the main concepts look like this:

If we saw that satellites typically shut down star formation somewhere near first pericentre, for instance, that would point to the removal of gas by ram pressure or tides being an important driver of their evolution. On the other hand, if we saw star formation shut down around apocentre, the implication would be that it’s not gas removal that’s directly regulating star formation, but instead that the cutoff of the supply of fresh gas (with the remaining gas supply being slowly depleted through star formation) that’s more important. If we could further work out how the connection between orbit and star formation history depends on the mass of the cluster, the mass of the satellite, and so on, we should be able to come up with a fairly complete picture of satellite galaxy evolution (relative to the evolution of non-satellites, at least). This broad topic is something I’ve been working on, on and off, since 2011.

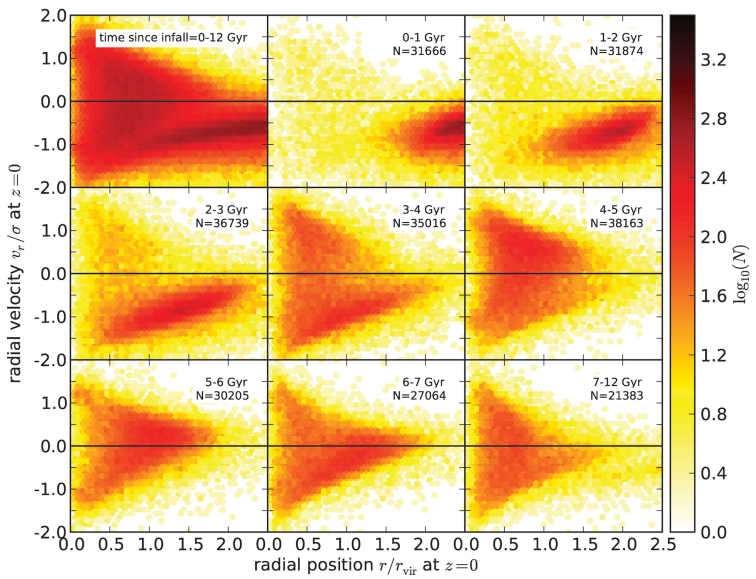

In my very first research paper, the main goal was to find a better observational proxy for the orbital state of satellites. At the time it was known that radial offset from the centre of the host system correlates with time since accretion onto the system, and there were a small number of papers pointing out that the velocity offsets of the satellites should also carry information. I took this relatively new idea and ran with it by cataloguing the orbits of satellites of galaxy clusters from an N‑body simulation. Fig. 3 from that paper (Oman et al. 2013) conceptually summarizes this - satellite galaxies with different infall times occupy different regions of a suitably normalised phase space coordinate plane. This is before accounting for projecting the system onto the sky, which makes the separation between the various regions a lot less distinct, but conceptually you can still assign a probability for being on a particular orbit according to a set of measured phase space coordinates.

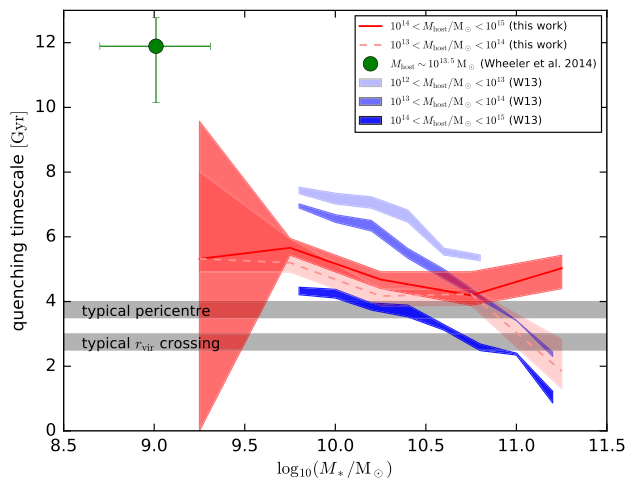

The obvious next step from here is to apply these probabilistic orbit assignments to some observed galaxies and try to back out a correlation with their star formation histories. I got as far as a proof of concept for this by the end of my MSc, but it took a few more years juggling the work with my PhD projects to arrive at something more polished (Oman & Hudson 2016). In the end I found that more massive satellite galaxies shut down star formation sooner after being accreted onto their host systems, summarised in Fig. 9 of that paper:

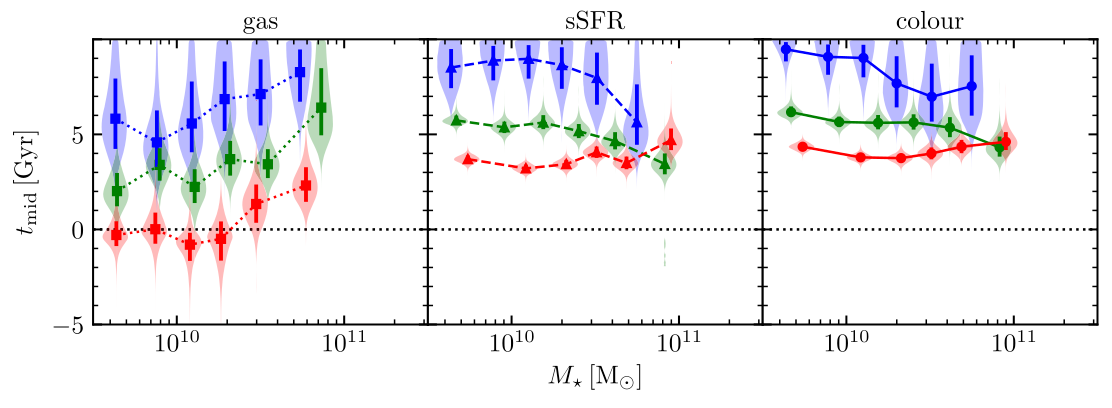

This was broadly in line with the very influential work of Andrew Wetzel a few years prior, but with a completely independent methodology (not just that we did it separately, but the approach is also quite different). I set this line of research aside for a few years but returned to it as a postdoc in Groningen, this time to make some improvements to the methodology (notably re-defining the reference point along the orbit from ‘infall’, which is ambiguously defined, to ‘first pericentre’) and also fold in direct observations of gas content to see whether we could tease out a connection between the orbit, gas content and star formation simultaneously. The other novelty was an effort to validate the analysis on a mock catalogue drawn from Yannick Bahé’s Hydrangea simulations of galaxy clusters. The end result is, I think, very neat, summarized in Fig. 10 of the paper (Oman et al. 2021):

The left panel shows that gas (in this case, atomic as traced by 21-cm emission) is stripped around (for clusters in red) or after (groups in green/blue) the first pericentric passage, while star formation as traced by Balmer emission lines (centre panel) or broadband colour (right panel) shuts down a bit later. Our interpretation is that a substantial amount of gas is stripped around first pericentre, at least in cluster satellites, but enough gas (possibly molecular rather than atomic) is retained to fuel star formation for a couple of billion years longer. Along the way we learned that there were some subtle flaws in the methodology of our earlier work (Oman & Hudson 2016) that meant that the detailed results and the interpretation were essentially wrong. You can check out Sec. 6.2.1 of the 2021 paper if you want all of the gory details. If I’d been more careful back in 2016 could I have spotted the flaws? I don’t think so - it took making some fundamental changes to the method to reveal the issues. Using ‘infall’ as a reference time isn’t wrong (so we had no pressing reason to do anything else), but it really does complicate things. Likewise, we figured that our assumptions around the stellar-to-halo mass relation were imperfect but probably good enough (they weren’t), but didn’t have a good idea to test this at the time. Perhaps I should have spotted the fact that our simulations didn’t have quite enough resolution for the lowest-mass galaxies we were using in observations - I’ll chalk that one up to inexperience.

Since that 2021 paper I haven’t done much on this topic myself, but have been involved as a collaborator or supervisor in a couple of things. Amit Upadhyay, that I co-supervised with Scott Trager for his MSc in Groningen, wrote a paper (Upadhyay et al. 2021) showing that there’s a lot of potential to use more observational information on the star formation history side of things - an aspect that I’ve pretty much always reduced to a single colour or SFR measurement in my own work. Amit instead used detailed star formation histories to track the buildup of stellar mass throughout the orbit. The tradeoff was that we greatly simplified the modelling of the orbits, mainly because there isn’t yet a big enough observational dataset of detailed star formation histories to really make use of the statistical power of full orbit libraries from simulations. But there will be in the not-too-distant future.

Azi Fattahi and I had long talked about applying some of the ideas I’d been developing with groups and clusters of galaxies to satellites of Milky Way-mass galaxies. We figured that for the Milky Way itself you could do much, much better with orbit integration based on Gaia proper motions and radial velocity measurements than what the statistical constraints from phase space coordinates could offer. But for Andromeda we don’t have Gaia, so that seemed like a promising target. Once again statistically large samples of satellites with detailed star formation histories aren’t available, but there is some additional information in terms of phase-space coordinates: we can measure reasonably accurate distances, which no only gives a 3D positional offset but also breaks a degeneracy in the sign of the radial velocity measurement. We offered this as an MPhys project and Alex Cooke did a very diligent job of it - there’s an advanced draft that we’ll hopefully submit for publication soon.

I was also peripherally involved in Andrew Reeves’ MSc work (supervised by my own MSc supervisor Mike Hudson, back in Waterloo). In his work (Reeves et al. 2023) the central idea is to use two independent tracers of the star formation history - in this case the current star formation rate and the mass-weighted stellar age - in the same analysis, connecting both back to the orbital histories of satellites in groups and clusters. It turns out that when we did this, the long-standing degeneracy between the time when star formation shuts off and how long it takes to do so (abrupt shut down vs gradual) was broken. The picture this led to was a lot of damage being done to satellite galaxies around their first pericentric passage (we were mostly in massive cluster hosts) but hints that they still manage to hang on to enough gas to continue star formation for a couple of billion years after this. This is a nice complement to what I found looking directly at the gas content (Oman et al. 2021). Looking forward, you could keep adding more measurements (colour in many bands, SFR, mass-weighted age, HI mass, CO mass, the list of options is pretty long…), but I think that at least on the star formation history side the more productive way forward will be to use estimates of the full star formation histories of large samples of galaxies that we’ll hopefully get from large spectroscopic surveys in the coming years. Folding in direct observations of gas is still an interesting angle, mind you, and will also be more feasible as wide-field sub-millimetre and radio surveys get easier to do.

More on the theory side of things, Toli Zadvornyi did a BSc project and MSc thesis with me (co-supervised by Marc Verheijen in Groningen) looking at a feature that stood out for a long time as interesting to me, but I never got around to digging into much myself: low-mass satellite galaxies shut down their star formation quickly, and so do very massive ones, while the intermediate-mass ones tend to survive longer. This is a bit simplified since we don’t tend t observe the lowest mass satellites around the most massive hosts and vice-versa, but after squinting at the relevant figures in the literature for long enough I, at least, am convinced of the qualitative feature. That the trend turns over at intermediate masses suggests that we’re seeing the transition between two physical processes regulating star formation. To mock up a quick qualitative picture, you could imagine that low-mass galaxies are so fragile that the slightest perturbation is enough to shut down star formation, while for the most massive satellites it’s the cutoff of the supply of fresh gas that does it - they don’t tend to have a big enough gas reservoir to sustain star formation for very long without replenishment. The intermediate-mass satellites would occupy a sweet spot in this picture: deep enough potential well to be fairly robust against the harsh environment of a satellite galaxy, yet with a long enough gas consumption timescale to keep star formation going for a long time even in the absence of fresh gas. Toli worked through backing this qualitative picture up with detailed theoretical work tracking the evolution of galaxies in the EAGLE simulations. It turns out others were working on similar ideas - Ruby Wright put out a paper towards the end of Toli’s projects that reaches many of the same conclusions as we did, also using EAGLE. There are still a few gems of insight from Toli’s work that would be nice to write up, but he’s moved on to a career in marine noise pollution mitigation, so I guess that task falls to me, when I can find the impetus.